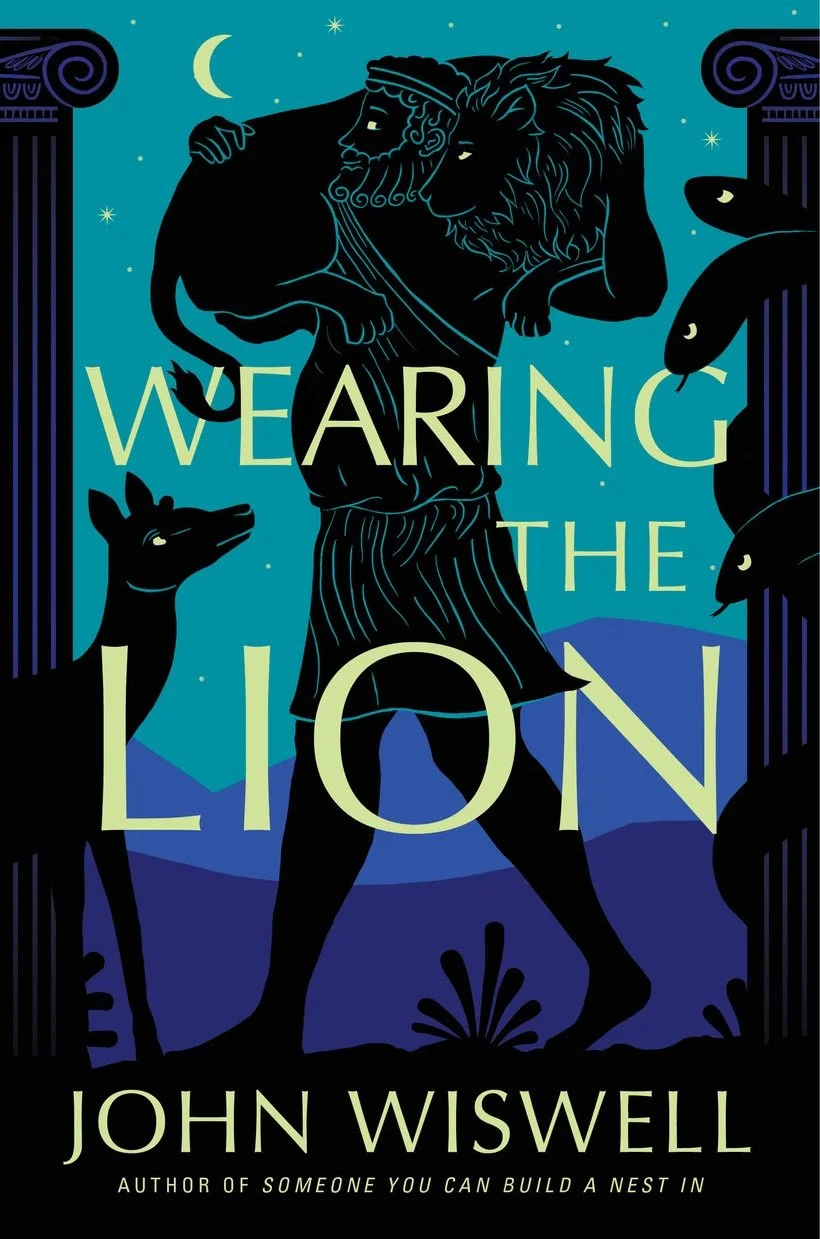

Communing with Monsters: An Interview with John Wiswell, Author of Wearing the Lion

John Wiswell’s Wearing the Lion is a retelling of Greek mythology that is sharply contemporary yet roils with the magic of ancient gods. Heracles prays to his Auntie Hera (the goddess), and she speaks back: in jealousy, with a sneer, and then, finally, with deep humility followed by a reinvention—a reclamation!—of her very self. Did you catch that? A god can learn and grow and change.

Both Hera and Heracles take tremendous journeys through ancient Greece, meeting monsters and gods (with a few hijinks), but also through the deepest of grief, ultimately evolving to find something that is not quite redemption but a new understanding of human emotion and the deep capacity for forgiveness—all while forging relationships that are strange but beautifully strong.

I spoke with John about radical forgiveness, disability, found family, and the profound way his Heracles wins battles by flipping conflict into friendship.

Allison Wyss: I wonder if you could talk about your relationship to the mythology that you’re retelling. Are these stories that you grew up with or did you come to them later on?

John Wiswell: Mythology and folklore were some of the first things my parents read to me, and Heracles was the first character to captivate me. As a little kid, he was aspirational. Don’t you want to be the strongest person in the world?

But his labors pit him against an array of creatures that fascinate in their own way. As I grew up, I thought about how similar Heracles was to those monsters. Many of them were created by gods, or were the gods’ direct children. Heracles was just another unusual being. Could he ever commune with them?

AW: The way this version of Heracles responds to the monsters is my favorite thing about the book. After being tricked into killing his own sons, in his grief and in his guilt, Heracles finds he can’t commit violence. And so he befriends the mythological creatures instead of fighting them.

JW: This is one of the reasons I wrote the book in the first place! Men in fiction are so often vessels for violence. We have an abundance of male role models to get revenge, or to be emotionless in “doing what needs to be done.”

I wanted to model a different kind of person. A man with a rich emotional life, whose greatest strength isn’t inherited from Zeus, but lies in his network and caring for others. Someone who can make space for others, and in doing so learn about the cosmic stakes around him and prepare in ways that a brute couldn’t. That all comes from his own pain. You cannot simply toughen up to the point where trauma won’t hurt you. I’ve worked with too many veterans to suffer that illusion. It was more interesting to me to put a man on the path of revenge who refuses to hurt anybody. Who realizes the whole narrative he’s in won’t help anyone, and so he has to upend it. It’s a herculean labor.

AW: Why do you think so much of Western literature relies on battle scenes, whether physical or intellectual, or “overcoming” an adversary?

JW: I’ve enjoyed plenty of violent stories. I wouldn’t say there is no place for them. But it’s worth wrestling with how much of fiction is conflict-driven and how frequently that conflict is empty and meaningless, or doesn’t give us anything more than the passive stimulation of bloodshed. Sometimes I worry that it deadens us. There’s also the long history of literature and the arts laundering conquest. It makes one skeptical of stories that valorize harming one group or another.

In a beautiful way, those same narrative tools can let us challenge toxic norms. They can inspire us to refuse to be deadened to each other and to undermine the normalization of violence towards anyone authority wishes to exploit. It all depends on what an author wants to do with their characters.

AW: Let’s talk about those mythological creatures that Heracles befriends, such as Logy (a hydra whose mental health and pain management require frequent fiery decapitations) or Boar (who is shaped like an aging man but knows he is really a boar), among others. They have all sorts of different bodies, and different talents, and different obstacles. But they all have value and worth—to Heracles, to the reader, and to each other. And they find ways to achieve what must be done—sometimes working together, sometimes parceling different tasks to different members. Can you talk about what their portrayal might have to say about disability justice?

JW: Monstrosity has always been interwoven with disability. Look at how many monster designs are just some dude with a bad skin condition. The limp of the mummy. The erratic emotion of the werewolf. Even as a little kid, I recognized how many things we were supposed to dislike about people were coded into monsters. That’s part of why children like pretending to be them. It lets them try on forbidden identities.

Having Heracles embrace the creatures he was sent to fight lets me do several things. Firstly, it lets him dwell on his own disabling trauma and make the first steps to realizing he has things in common with “monsters.” Further, if he can’t comfort himself, he can still bring comfort to them. The Nemean Lion isn’t so bad when he’s blissed out from head scratches.

Migraines, PTSD, amputation—these are just parts of being alive. By having creatures with disabled-like features bond with actual disabled humans, I’m letting the metaphor for the thing meet the thing. And that’s one of my favorite stories to write. We can make a little meaning together.

AW: I love that.

But none of this means the story is “soft.” Hera and Heracles both commit atrocities. There is a lot of violence. And there is also grief, atonement, love, community, and radical forgiveness. Wearing the Lion gives grace to characters who have committed the most horrendous of crimes. And on a smaller scale, characters are also allowed to be messy even after they’re forgiven for the “big” thing and taken into the family. Characters are allowed to make mistakes and then be sorry and repair the relationship.

JW: Heracles’s entire myth lies in the shadow of a tragedy for which there is no restoration. His children cannot be brought back to life. Megara’s and his traumas cannot be erased. Even what the Fury went through that day may have irrevocably changed her.

I’m interested in what we do when there is no singular right thing. In that absence, revenge often raises its head, which is glamorized to obfuscate how it’s often worse than useless. Hera begins by freezing up and ceasing to do additional harm, but just because you stop doesn’t mean you’ve remedied anything. You have to do the work.

What she and Heracles learn, at around the same time, is that carrying the confusion and pain can leave you sympathetic for people you’d never have looked at before. You can feel monstrous. And those who have been treated as monsters may understand you better than anyone else. But the two of them process that knowledge in very different ways.

AW: Yes, Hera’s journey is perhaps even more tumultuous than Heracles’s. Hera starts out as a bit of a cliché—the jealous wife—but then she evolves throughout the story and ends up incredibly complex. I love getting to go on that journey with her, but did you worry, starting that way, that readers might not be patient enough to see her as more than her jealousy?

JW: In mythology, Hera all too frequently gets flattened. It is easy to reduce it to this: Zeus is what the rich men of Ancient Greece wanted to be, and Hera is what they hated about their wives. You can see it in many ancient stories about the two of them. But the whole truth is wider than that. There were periods where Hera was worshipped more widely than any other god in the pantheon. Ancient Greeks had a much more complicated relationship with the idea of her.

That is an invitation to dig into Hera as a much deeper character, who has a depth that reflects the needs and fears of her people. She procrastinates by making sure towns of children are fed; she kills time by bringing justice down on the heads of unworthy kings. Every move through the mortal world says something about her psyche.

Hera is one of my favorite characters I’ve written. At the outset, I hope that she is funny enough in her takedowns and that her rage at Zeus is relatable enough so that readers will give her time to reveal her other layers. Does she make mistakes? Yes. Unforgivable ones. But even in the first chapter, Granny believes Hera is capable of more and deserves more. And you can see that Hera cares more deeply than she lets on, even for Zeus. She sees his mysterious injury, and all her ire is derailed.

I trust readers to see the clues and unearth what’s really going on in her psyche. Hera is trapped in her role in mythology, which is hard for her to appreciate, as the Queen of Olympos. Outgrowing her own legend is the start of something special for her.

AW: While the story begins with Hera and Zeus’s toxic marriage, we see an incredibly healthy respect of boundaries from the start with Heracles and Megara. Then we see Heracles build a new sort of family with the monsters he befriends. And we see their troubles—but we see them work through them. What is the book saying about found families and community bonds and building healthy relationships?

JW: Especially early in the novel, people assume Heracles is foolish in his devotion to Hera. But he embraces virtues derived from her, both in how he treats his biological family and, later, his found family. He is pursuing things about Hera that she’s lost touch with and that she has to reconnect with. Remember, Hera also starts the story with a found family that loves her: Atē and Granny.

But between her own insecurities and Zeus’s scheming, she’s distracted herself from what those people love about her. Meanwhile, Heracles has built his life out of these ideals that Hera is rediscovering: that family can come to us from many angles, many of them unexpected and difficult, and if we’re lucky, they can work miracles.

AW: Because I see this book doing it both ways—as we’ve just discussed!—I wonder if you think a story makes a stronger case by normalizing a way of being from the start or by putting a character on a journey to learn it.

JW: Since I did it both ways, you can guess that I see the merit in both, right?

The power of normalizing a point of view by starting a character in a place of virtue is strong. We love a Mary Poppins or an Uncle Iroh. Prometheus cared for humanity’s suffering from the start. And then sought to steal fire.

But one of the most powerful things in storytelling is watching people grow. Having them grow in reaction to a theme reaches things that pure normalization doesn’t. Legolas and Gimli overcoming their prejudice to become brothers in arms hits differently, right?

In this book, I put Heracles and Hera in very different places so they could contrast each other in a duet of those themes. The contrast can let you do more, including showing the limitations of both approaches. No matter how lovable or virtuous someone is, people carry flaws with them. I’d rather not deny those truths about us, but have the characters grapple with them.

Allison Wyss (@wyssallison) is the author of the short story collection, Splendid Anatomies (Veliz Books), which was a finalist for the Shirley Jackson Award. Her stories, essays, and interviews have appeared in Wigleaf, Cincinnati Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, Lit Hub, The Rumpus, and many other places. Some of her ideas about the craft of fiction can be found in a monthly column she writes for the Loft Literary Center, where she also teaches classes.

John Wiswell (@john_wisell) is a disabled writer who lives where New York keeps all its trees. He won the 2021 Nebula Award for Short Fiction for his story, “Open House on Haunted Hill,” and the 2022 Locus Award for Best Novelette for “That Story Isn’t The Story.” He has also been a finalist for the Hugo Award, British Fantasy Award, and World Fantasy Award. He is the author of Someone You Can Build a Nest In, a Nebula nominee and Year’s Best pick by NPR and The Washington Post, and Wearing the Lion. He can be found making too many puns and discussing craft on his Substack, johnwiswell.substack.com.